What are anxiety disorders

Center for Children with Special Needs Tufts-New England Medical Center What Are Anxiety Disorders? Anxiety is a normal response to stress, whether real danger or a perceived loss of self-esteem or control. It helps one deal with a tense situation, study harder for an exam, or keep focused on an important project. In general, it helps one cope. But when anxiety causes an excessive, irratio

AMERICAN JOURNAL OF MEDICAL GENETICS PART A

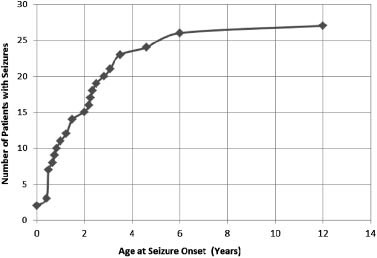

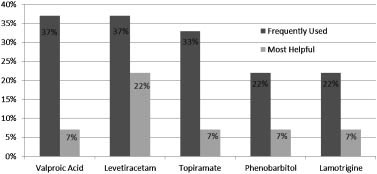

children had onset of clustered epileptic spasms after infancy(‘‘late-onset spasms’’) and one of these children had an EEGconsistent with ‘‘modified hypsarrhythmia.’’ Of these four chil-dren, one had onset of ‘‘massive myoclonic jerks’’ at age 13 monthsthat appeared photosensitive in nature, and clustered tonic spasmsonly emerged later at age 4 [Cerminara et al., 2010]. The last of thesefive children had onset of partial clonic seizures at age 5.5 yearsfollowed by the appearance of clustered tonic spasms in flexion1 year later [Cerminara et al., 2010]. This prior data, though basedon a very small sample size, would suggest that children with PKScould be prone to later onset clustered spasms as a particularepileptic phenotype. Other case reports (Table I) suggest alternativeseizure semiology. For example, Smigiel et al. [2008] reporteduncategorized seizures in a neonate with PKS, while Spelemanet al. [1991] described two patients with generalized seizures whowere treated with valproic acid. Clearly, the existing informationavailable with respect to the seizure and epilepsy characteristics in

FIG. 1. PKS patient facial characteristics. Note hypertelorism,

PKS (Table I) is limited and presented in a fairly inconsistent and

temporal balding, forehead prominence, and macrostomia.

AMERICAN JOURNAL OF MEDICAL GENETICS PART A

children had onset of clustered epileptic spasms after infancy(‘‘late-onset spasms’’) and one of these children had an EEGconsistent with ‘‘modified hypsarrhythmia.’’ Of these four chil-dren, one had onset of ‘‘massive myoclonic jerks’’ at age 13 monthsthat appeared photosensitive in nature, and clustered tonic spasmsonly emerged later at age 4 [Cerminara et al., 2010]. The last of thesefive children had onset of partial clonic seizures at age 5.5 yearsfollowed by the appearance of clustered tonic spasms in flexion1 year later [Cerminara et al., 2010]. This prior data, though basedon a very small sample size, would suggest that children with PKScould be prone to later onset clustered spasms as a particularepileptic phenotype. Other case reports (Table I) suggest alternativeseizure semiology. For example, Smigiel et al. [2008] reporteduncategorized seizures in a neonate with PKS, while Spelemanet al. [1991] described two patients with generalized seizures whowere treated with valproic acid. Clearly, the existing informationavailable with respect to the seizure and epilepsy characteristics in

FIG. 1. PKS patient facial characteristics. Note hypertelorism,

PKS (Table I) is limited and presented in a fairly inconsistent and

temporal balding, forehead prominence, and macrostomia.

AMERICAN JOURNAL OF MEDICAL GENETICS PART A

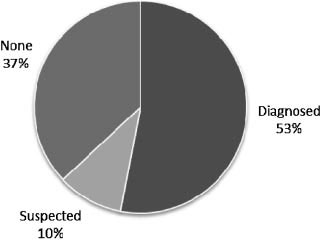

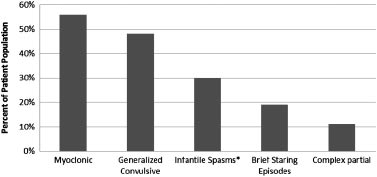

TABLE III. Seizure Patient Characteristics (n ¼ 27)

AEDs, antiepileptic drugs.

AMERICAN JOURNAL OF MEDICAL GENETICS PART A

TABLE III. Seizure Patient Characteristics (n ¼ 27)

AEDs, antiepileptic drugs. mal, often exhibiting a so-called ‘‘split-brain’’ pattern [Ohtsukaet al., 1993; Aicardi, 2005].

mal, often exhibiting a so-called ‘‘split-brain’’ pattern [Ohtsukaet al., 1993; Aicardi, 2005].